Quartet in G Major, K. 387

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 – 1791)

Mozart’s musical genius soon became apparent to his musician father. At the tender age of six Leopold Mozart took his son on the first of

Mozart’s string quartets span his life—from the earliest at age 15 to the more sophisticated compositions a year before he died. They also trace the development of the genre from light background pieces for entertainment to one of the primary instrumental genres of the high Classic period

Mozart modeled his works on those of Haydn, yet Haydn “learned from Mozart how to compose quartets.” Theirs was a relationship of reciprocal influence and stimulation. (Ulrich

A ten-year lull followed Mozart’s thirteen youthful quartets; he renewed his interest in the quartet genre because of his friendship with Haydn, who published his Op. 33 quartets in early 1782. Mozart finished his Quartet in G Major, K. 387, at the very end of 1782. It is the first of the Haydn quartets, a set of six quartets that Mozart composed during his first years in Vienna to honor Joseph Haydn: “To my dear Friend Haydn. A Father, having resolved to send his children into the great world, felt obliged to confide them to the protection and guidance of a highly celebrated Man, especially when by good luck he was at the same time his best Friend…Here then they are, my six children, celebrated Man and dearest Friend!

The sunny first movement sonata-allegro form Allegro vivace assai contrasts diatonic passages with chromatic runs. Mozart’s grave Menuetto alternates loud notes or phrases with soft ones in quick succession. The darker trio section begins with a rising figure in a minor key. Dynamic contrast is also essential in the serene Andante cantabile. The Molto allegro finale combines the retrospective polyphonic techniques of the fugue with Classical sonata principles. Throughout the movement fugato episodes alternate with more homophonic interludes. Mozart deftly composed these fugal passages within a sonata-allegro form, bringing the quartet to a quiet and unassuming closure in the final measures

Reactions to Mozart’s Quartet in G Major were positive. Giovanni Paisiello stated, “This is the most magnificent piece of music I ever saw in my life.” Haydn on hearing a performance of the quartet wrote to Mozart’s father, Leopold: “I tell you before God, and as an honest man, that your son is the greatest composer I know, either personally or by reputation; he has taste and moreover the greatest possible knowledge of the science of composition.”

Quartet in F Major

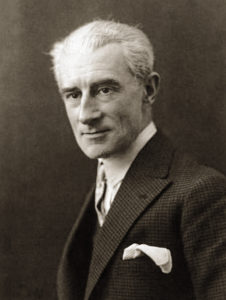

Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937)

Frenchman Maurice Ravel began composing around age twelve. He studied at the Paris Conservatory as a preparatory student in piano; in

The Quartet in F Major, composed while Ravel was still a student at the Conservatory, is an early work, his first chamber music composition, and one of his first works with no programmatic or literary title. It is dedicated to his former composition teacher and lifelong friend Gabriel Fauré. In his autobiography he stated, “My Quartet in F, 1902-1903, responds to a desire for musical construction, which undoubtedly is inadequately realized but which emerges much more clearly than in my preceding compositions.” In the Quartet Ravel already shows his mastery of traditional forms with its four-movement classical structure.

The prevailingly lyrical opening movement, in sonata-allegro form, presents two themes that occur later in the Quartet. The second movement is a playful scherzo with swiftly moving pizzicatos and cross-rhythms created by the outer voices in 3/4 meter against the inner voices in 6/8 meter. The effect evokes the sounds of bells or perhaps a Javanese gamelan (which Ravel heard at the Paris International Exposition of 1889). A moody trio with “wavering tonality” provides contrast. A lyrical and rhapsodic slow movement follows; Ravel manipulates fragments of the first movement’s main theme against a serene harmonic backdrop. He achieves coloristic effects with the instruments playing on the fingerboard or entirely in the treble range. The vigorous fourth movement provides dramatic restless contrast with its quintuple meter. Ravel alternates these agitato passages with lyric material derived from the first movement. The turbulence of the opening bars reasserts itself and the work ends vigorously.

The work premiered in March 1904 by the Heymann Quartet at a concert of the Société Nationale de Musique and opinion was sharply divided. Fauré was not greatly taken with the piece. Pierre Lalo dismissed it as derivative: “… in its harmonies and successions of chords, in its sonority and form, in all the elements which it contains and in all the sensations which it evokes, it offers an incredible resemblance with the music of Debussy.” Jean Marnold praised it, asserting “one should remember the name of Maurice Ravel. He is one of the masters of tomorrow.” And Debussy is said to have exclaimed: “In the name of the gods of music and my own, do not change one thing in your quartet!”

Quartet in F Major, Op. 96, “American”

Antonín Dvořák (1841 – 1904)

Czech composer Antonín Dvořák, known for frequently employing features of the folk musics of Moravia and his native Bohemia, showed

During his sojourn in America, various experiences provided impressions of American folk music, which influenced the vocabulary for his American compositions. In the spring of 1893 Dvořák attended Buffalo Bill Cody’s “Wild West” show in New York where he heard a group of Oglala Sioux; he heard the “pathetic, tender, passionate, melancholy, solemn, religious, bold, merry, gay or what you will …” sentiments of the Negro spiritual; and in Iowa he heard a performance by the Kickapoo Medicine Company

After a hectic year in New York City as director of the conservatory, Dvořák and his family spent the summer of 1893 in the small town of Spillville, Iowa, home to a Czech immigrant community. Dvořák, delighted and charmed by the rural environment, was relaxed and energized here: “The children arrived safely from Europe and we’re all happy together. We like it very much here and, thank God, I am working hard and I’m healthy and in good spirits.” He sketched the quartet in only three days and finished it thirteen days later. Dvořák defended the apparent simplicity of the piece: “When I wrote this quartet … I wanted to write something for once that was very melodious and straightforward, and dear Papa Haydn kept appearing before my eyes, and that is why it all turned out so simply. And it’s good that it did.”

The opening theme of the sonata-allegro first movement, marked Allegro non troppo, is based on a pentatonic (5-note) scale played by the viola, with shimmering chords in the accompanying instruments. “It is light-hearted and playful, smilingly gay and overflowing with high spirits or idyllic calm.” (Šourek) The simple pentatonic melody of the Lento second movement recalls spirituals or Native American ritual music. The first violin introduces the melancholy theme and the cello repeats it; the second violin and viola provide a rocking accompaniment. Dvořák developed this thematic material in a happier extended middle section. Dvořák built the Molto vivace scherzo from a single theme, a sprightly tune with off-beats and cross-rhythms. A slower, more lyrical variant of the first theme provides contrast in the ABABA form. Dvořák also quoted a bird song high in the first violin. The quartet ends in a whirl of good spirits and jollity: the Finale: Vivace ma non troppo is a traditional rondo with a cheerful pentatonic principal theme and sharply accented chords. A quiet chorale-like episode may have been inspired by hymns that Dvořák played on the organ at St. Wenceslaus Church in Spillville. The quartet ends with a return to a festive mood.

After an early performance, author Henry Edward Krehbiel wrote that the quartet “is not profound or heavily weighted with emotion, but it is full of ingenuity, replete with gracious fancy, clear as crystal and inspiriting in its unalloyed happiness.”

The work reveals Dvořák’s depth of feeling, the resourcefulness of his technique, and his boundless imagination. Clear forms, subtle contrasts of texture and tone color, and great melodic charm combine to place (it) among his finest works. The American Quartet is deservedly one of the most popular of late nineteenth-century chamber music compositions.” (Ulrich)

Linda Russell, a member of Maine Music Teachers Association and an independent piano teacher, lives in Portland with her longtime spouse